What Happened During and After the Tulsa Race Massacre

At this time, rumors were still circling around that there was going to be a possible lynching and people from the Greenwood community were getting nervous about this because they were thinking that it was probably going to happen unless they stood their ground. Showing up at the courthouse around 10 P.M, 75 members of the Greenwood community had returned. They had come back to make sure that nothing happened to Rowland. Unfortunately for the Greenwood Community, there were only 75 of them. When they got to the courthouse, they saw that there were over 1,500 angry white people. According to witnesses, a white man is alleged to have been yelling at one of the armed black men to surrender his pistol. When the man refused, a shot was fired.

Some people say that it may have been an accident or it was meant to be a warning. But, because of this one shot, it turned many people to fire their weapons at one another. After shots were fired, chaos broke out. Those who came from Greenwood retreated on foot and some in vehicles, back to Greenwood. Instead of the now armed, white mob leaving the black men alone, the white mob decided to follow the black men back into Greenwood. Many of the white mobsters had stopped to loot local stores for additional weapons and ammunition.

Along the way, the angry white people shot any bystanders who were black that they saw. Panic began to set in because the angry white mob began firing on black people that they saw, which would then turn quickly into an angry white riot. At around 11 P.M., members of the National Guard Unit began to assemble at the armory to organize a plan to subdue the rioters. Several groups were deployed downtown to set up guard at the courthouse, the police station, and other public facilities.

They appeared to have been deployed to protect the white districts, which were adjacent to Greenwood, and not there to protect Greenwood itself or the black community at all. They were there to protect the angry white people. The National Guard rounded up numerous black people and took them to the Convention Hall on Brady Street for detention as the evening proceeded. Why were they being arrested and detained? They were being arrested simply because they were black. There were many people that were being arrested and detained who were not armed and who were minding their own business, but were black.

Many important and famous white Tulsans also participated in the riot including Tulsa founder and Ku Klux Klan member, W. Tate Brandy, who participated in the riot as a night watchman. Throughout the morning of June 1, 1921, small groups of whites made it into Greenwood by car and some by foot. They were shooting with no reason into businesses and residences, throwing lighted oil rags into several buildings along the streets and setting whatever was in their path on fire. Crews from the Tulsa Fire Department came to town to put out the fires, but they were turned away at gunpoint by the angry white mob. The white mob would not allow for the firefighters to enter the town to put out the fires.

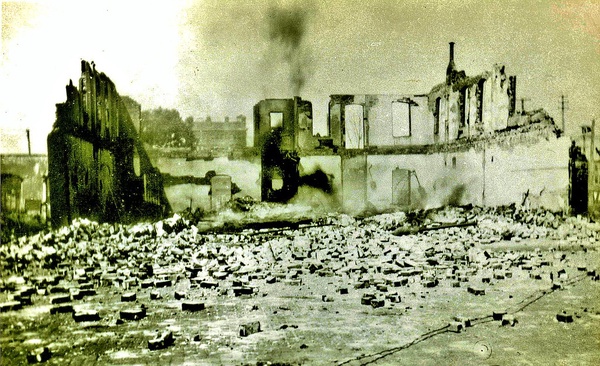

Many residents inside Greenwood began to get their handguns or whatever they could find to defend their neighborhood, while a lot more residents tried to flee the town completely. Throughout the night though, both sides continued to fight. According to a Red Cross estimate, approximately 1,256 houses were burned throughout the night, 215 were looted but not set on fire, two newspaper companies, schools, a library, a hospital, churches, hotels, stores, and many other black-owned businesses were destroyed or damaged by fire. It is believed that one hundred to three hundred people were killed during this massacre.

Numerous eyewitness accounts described airplanes flying above the town, firing their rifles out of the airplanes and dropping fire bombs on buildings, homes and families. Law enforcement personnels were thought to be aboard at least some of those airplanes, but there were some flights that were said to be privately owned. But, it was not known as to who the planes were privately owned by. “Greenwood survivors recount disturbing details about what really happened that night. Eyewitnesses claim ‘the area was bombed with kerosene and/or nitroglycerin,’ causing the inferno to rage more aggressively. Official accounts state that private planes ‘were on reconnaissance missions, they were surveying the area to see what happened.’ ” According to eyewitness accounts from survivors during Commision hearings and manuscripts by eyewitnesses discovered in 2015, on the morning of June first at least a dozen or more planes curled the neighborhood and dropped burning turpentine balls on an office building, a hotel, a gas station and multiple other buildings (The Devastation of Black Wall Street).

The white men were firing rifles at young and old black residents, gunning them down in the street. Law enforcement officials stepped in and gave a little statement. They were saying that the airplanes were put there to provide safety and protection against a “N-word uprising.” In other parts of the city, the angry white rioters went to the homes where there were a lot of middle-class white families who employed black people in their homes as live-in cooks and servants. The white people demanded the middle-class white families to hand over their employees to be taken to detention centers around the city.

Because the white people showed up with rifles and weapons, many of the middle-class white families complied with the demands. If they didn’t comply, they were harassed by the rioters and their homes would be vandalized. Then, the governor of Oklahoma had ordered the National Guards to come in. That day, Oklahoma City was put under martial law which would be established that day; so, troops were pretty much arresting everyone who was black and then requiring detainees to carry identifications cards on them.

It is said that as many as 600 black Greenwood residents were held at three local facilities. They had the Convention Hall which would be now known as the Brady Theater, the Tulsa County Fairgrounds which then was located about a mile northeast of Greenwood, and McNulty Park which is a baseball stadium. Some black people were held at these locations for as long as eight days. Around 11:30 A.M., Martial law was declared and by noon, the troops had managed to suppress most of the remaining violence. In the hours after the Tulsa Race Massacre, all charges against Dick Rowland were dropped. Sarah Page, the woman who was working the elevator, decided to drop the charges against Rowland. “While it is still uncertain as to precisely what happened in the Drexel Building on May 30, 1921, the most common explanation is that Rowland stepped on Page’s foot as he entered the elevator, causing her to scream” (Tulsa Race Massacre).

Rowland was kept safely under guard in the jail during the riot. He ended up being exonerated and left Tulsa the next morning and reportedly never returned. 35 city blocks were completely destroyed, over 800 people were treated for their injuries and the official tally of deaths in the massacre was 36 people. Historians now consider the death number too low. The Tulsa Race Massacre stood as one of the deadliest riots in U.S. history behind the New York Draft Riots of 1863, which killed 119 people in total.

In the years to come, the black community worked to rebuild their ruined homes and businesses. Segregation in the city only increased and Oklahoma’s newly established branch of the KKK grew in strength. The newspaper was trying to make it seem like the black community were the bad guys in this situation. For decades there were no public ceremonies, no memorials for the dead, or any efforts to acknowledge the events taking place between May 31 and June 1, 1921. Instead, there was an intentional effort to cover the whole thing up like it never happened. Tulsa Tribune was the newspaper who reported the story about Rowland in the first place and essentially caused the outrage.

They removed the front-page story of May 31st from its bound volumes which was essentially erasing it from its records like it never happened. Later, scholars discovered that police and state archives about the riot were completely missing as well. Until recently, as a result, the Tulsa Race Massacre was rarely mentioned in history books, wasn’t taught in schools or even talked about.

On the riot’s 75th anniversary in 1996, a service was held at the Mount Zion Baptist Church, which rioters had burned down to the ground and a memorial was placed in front of the Greenwood Cultural Center. An official state government commission was created to investigate the Tulsa Race Riot the following year. Scientists and historians began looking into long-ago stories including numerous victims buried in unmarked graves. In 2001, the report of the Race Riot Commission concluded that between 100 and 300 people were killed and more than 8,000 people were made homeless in those 18 hours in 1921.

Over the next year, local citizens filed more than 1.8 million dollars in riot related claims against the city by June of 1922. Despite the promise of funding, many people from the Greenwood community spent the winter of 1921 and 1922 in tents as they worked on rebuilding their neighborhood. The tents that they were living in were set up by the Red Cross. Most of the funding that was promised was never raised for the residents. They had struggled to rebuild after the violence and had little to no financial help. In order to continue to rebuild, a new fire code was said to be set in place to prevent another tragedy from happening. They were going to do this by banning wooden framed houses in place of the previously burned homes.

Because of this new fire code that was supposedly being set in place, all construction came to an abrupt stop and caused major delays. The Greenwood community was not allowed to rebuild until the new fire code was set in place. They kept sitting and waiting, but the fire code kept getting put off. It was getting put off on purpose because the Greenwood land was wanting to be taken over. The Reconstruction Committee simply failed to formulate a single plan moving forward. It left many of the residents prohibited from rebuilding for several months because it was going against the fire code.

City planners immediately saw the fire that destroyed homes and businesses across Greenwood as a really good thing. They thought of it as a bunch of open land and had plans for this new land. Because they were making plans of their own on what they wanted to do with the land area, they were showing a complete disregard for the welfare of affected residents. Plans were immediately made to rezone the burned area for industrial use. The Reconstruction Committee wanted to have the black landholders sign over their properties. A large central rail hub called the Tulsa Union Depot, was built where many of the homes and businesses which were destroyed less than two years later.

It is believed that the fire code was being blamed to prevent Greenwood community from building in this area because the white Oklahomians knew that they wanted to take this land over and they also did not want to give the black community 1.8 million dollars. So, they kept putting it off and eventually the people who were living in tents, trying to rebuild, had no money, no homes and were growing more and more exhausted, causing them to leave Greenwood. Some of the landholders were offered a very small compensation for their land. Because they had all this extra land now, it allowed them to build an even larger train depot where Greenwood used to be.

There were no convictions for any of the charges related to the riot when it came to the white rioters, but the black community paid a big price and a lot of them were detained. There were decades of silence about the terror, violence, and losses of this event. The riot was largely omitted from local, state and national histories. A young woman by the name Mary E. Jones Parrish, was an African American teacher and journalist from New York. She was hired to write an account of the riot. She was a survivor and had written about her experiences. She collected other accounts and experiences from other survivors as well. Parrish gathered photographs and compiled a partial roster of property losses in the African American Community. She then published “Events of the Tulsa Disaster,” which was the first book to be published about the riot.

Many who tried to share their stories to local newspapers, city newspapers, town newspapers, wherever they could, encountered pressure mainly by the white community to keep silent or they would take the story and do nothing with it. In February of 2003, five elderly survivors filed a suit against the city of Tulsa and the state of Oklahoma. This suit said that the state and city should compensate the victims and their families to honor their admitted obligation, which was detailed in a commission’s report. The federal district and courts dismissed the suit, citing the statute of limitation had been exceeded on the then 80-year old case because the state requires that civil rights cases be filed within two years of the event. The Supreme Court of the United States declined to hear the appeal.

In April of 2007, there was a push for the U.S. Congress to pass a bill extending the statute of limitations for this particular case given the state and city’s accountability for the destruction and the long suppression of material about it. The bill would be introduced and heard by the Judiciary Committee of the House, but it did not pass. In 2009, the bill was reintroduced as the John Hope Franklin Tulsa Greenwood Race Riot Claims Accountability Act of 2009. Then again in 2012, they introduced the bill, but it has not gotten out of the Judiciary Committee.

It was named in honor of the late Dr. John Hope Franklin who was a firsthand witness to the destructive impact that the riot had on the community. He made numerous contributions to the understanding of the long-term effects of the riot on the people and worked to keep the issue alive in history. According to the State Department of Education, it has required the topic in Oklahoma history classes since 2000. The riot has been included in Oklahoma history books since 2009 and it wasn’t required country-wide to learn about.

A bill in the Oklahoma State Senate requiring that all Oklahoma high schools teach about the Tulsa Race Riot, failed to pass in 2012. The people who were against the bill, claimed that schools are already learning about this riot and we don’t need to make it a bill. Studies show that U.S history classes from kindergarten to 12th grade devoted about 9% of their time to Black History in 2015. LaGarrett King, an associate professor of social studies education at the University of Missouri, states that not much has changed since then. In November of 2018, the 1921 Race Riot Commission was officially renamed the 1921 Race Massacre Commission. In April of 2020, nearly a century later, Tulsa plans to dig for suspected mass graves in a city owned cemetery that may have been used to dispose of the victims’ bodies and it is still believed that there is a mass grave somewhere.

Humanities, N. E. for the. (n.d.). The broad ax. [volume] (Salt Lake|\\\ City, Utah) 1895-19??, June 18, 1921, image 1. News about Chronicling America RSS. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024055/1921-06-18/ed-1/seq-1/

History.com Editors. (2018, March 8). Tulsa Race Massacre. History.com. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/tulsa-race-massacre

Branigin, A. (2019, October 8). Nearly 100 years later, Tulsa begins search for mass graves from 1921 Black Wall Street massacre. The Root. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.theroot.com/nearly-100-years-later-tulsa-begins-search-for-mass-gr-1838883790

Wikimedia Foundation. (2022, April 18). Tulsa Race Massacre. Wikipedia. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulsa_race_massacre

Hi! My name is Cynthia Wing. I am 15 years old and in 10th grade. This is my first year on the Spud. I am the daughter of Maria and Henry (step-dad)...