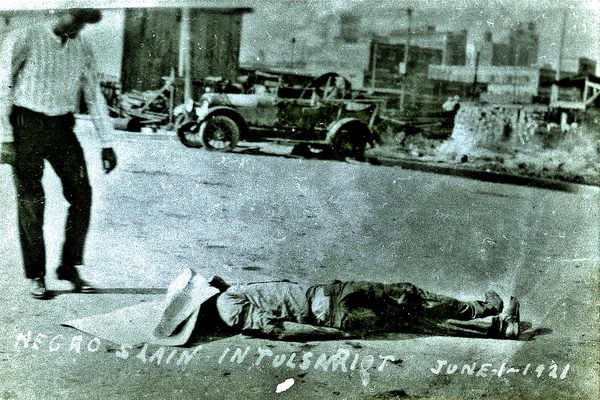

What Happened Before The Tulsa Race Massacre

With the return of many ex-servicemen coming back home, the first World War ended in 1918. In 1921, Oklahoma had a racially, socially and politically tense atmosphere. Civil Rights were still lacking for many people and the Ku Klux Klan was on the rise. Nearly 50 years after 1866, in 1915, “Colonel” William Joseph Simmons revived the Klan after seeing D.W. Griffith’s film Birth of A Nation, which portrayed the Klansmen as great heroes. The KKK was on the rise and becoming more and more popular and well known.

Tulsa, Oklahoma was a booming oil city. It supported a large number of affluent, educated and professional African Americans. This caused tensions in the city and a combination of factors played a part in all of this, but it was mainly racial tensions. Oklahoma was admitted as a state in November of 1907 by President Theodore Roosevelt.

The newly created state legislator passed Jim Crow’s laws, which were state and local laws that enforced racial segregation. In 1907, the Oklahoma Constitution did not call for strict segregation. But still, the very first law passed, segregated all rail travel and voter registration rules, which effectively disenfranchised (deprived of the right to vote) most of the black community. This meant that they were not allowed to serve on juries or in local offices. These laws were in place until after the passing of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965, which was sixty years after the Tulsa Race Massacre.

On August 14, 1916, Tulsa passed a law that mandated residential segregation by forbidding blacks or whites from living on any block where ¾ more of the residents were of the other race. The United States Supreme Court declared that this was unconstitutional. Tulsa and many other southern cities proceeded to establish and enforce segregation for the next three decades. The Ku Klux Klan had been growing in urban chapters across the country again since 1915. Tulsa had an estimate of 3,200 residents in the Klan by the end of 1921. The city’s population was about 72,000 in 1920.

Greenwood was a district in Tulsa, which was organized in 1906. It became so successful that it was known as “The Black Wall Street.” The black community had created their own businesses and services in this area, several grocery stores, two movie theaters, nightclubs, restaurants, numerous churches, and even their own newspaper. They had black professionals including dentists, doctors and lawyers who lived and worked in this area as well. Because the black community was not welcome in other towns, cities, or even to live on the same block as white people, they decided that they should start their own successful town and do it themselves. So, that’s what they did (The Devastation of Black Wall Street).

Greenwood residents selected their own leaders and raised capital there to support economic growth. This caught the attention of the white community. It fed into the racism that was going on because the white community didn’t like the fact that the black community was being more successful than they were.

A young black teenager named Dick Rowland, who worked as a shoe shiner, employed at a Main Street Shine Parlor. On May 30, 1921, he entered an elevator at the Drexel Building, which was an office building on South Main Street. It is believed that Rowland may have been trying to get to the only restroom in the building but it is still not clear as to what he was doing. The woman operating the elevator was a white woman named Sarah Page. Dick Rowland had entered the elevator and what happened on the elevator is still unknown. But, it is known that at some point while Page and Rowland were on the elevator, Page screamed and Rowland was seen running out of the elevator.

The man who was working the front desk in the building, ran over to the elevator and saw Sarah. The man said he saw her in a distraught (deeply upset or agitated) state and called the police. The police came out and questioned Sarah, but there was no written account of her statement that had been found. Most people believe that the police had determined what had happened between the two. The authorities conducted a subtle investigation of their own without doing the proper paperwork. After this incident, rumors started to swirl around the town.

Not long after the incident took place, it had circulated through the city’s white community about what supposedly happened on that elevator. A front page story from the Tulsa Tribune reported that police had arrested Rowland for sexually assaulting Page, but Rowland did not sexually asssult her. After the front newspaper came out, Rowland was scared for his life. An accusation alone could put him at risk of an attack by angry mobs of white people. Rowland knew his life was in danger now. Trying to hide out until hopefully things calmed down, he decided to stay with his mother, who lived in the Greenwood neighborhood.

The next morning after the incident, Rowland was located and arrested, and taken to the Tulsa City Jail. Because the jail was receiving threatening phone calls from people who were saying that they were going to kill Rowland, and to hand him over because they (the white people) were going to take care of him, he was transferred. As the night came, an angry white mob was gathering outside the courthouse where Rowland was at and they were demanding that the Sheriff should hand Rowland over. The Sheriff, Willard McCullough however, refused to hand him over and his officers barricaded the top floor to protect him.

The courthouse elevators were shut down and the remaining officers barricaded themselves at the top of the stairs with orders to shoot any intruders insight. The Sheriff decided that he was going to go outside and try to talk to the angry white people and try to calm them down. When he went to calm the mob down, he had no luck. The white people were not going anywhere unless he handed over Rowland. The angry mob wanted Rowland lynched (hung or killed), so they were protesting to lynch Rowland.

A few blocks away, members of the community gathered and discussed what was going on. They were trying to figure out what happened to Rowland, why everyone was angry, and what they were going to do to calm the crowd down and prevent them from lynching Rowland. At around 9 P.M., a group of about 25 armed black men, including some World War I veterans, went out to the courthouse to offer help guarding Rowland from the growing mob. It was thought that the black men were trying to start something by going down there, but the black men stated that the reason they went down there in the first place was because the main Sheriff, McCullough, personally told them that their presence was required at the courthouse.

Twenty-five of those black men went out there and the Sheriff turned them away saying that they were not needed, but ten witnesses said that they were just following the order from the Sheriff in the first place. So, the Sheriff went out making a public statement saying that he never asked for them to come, publicly denying that he gave any order for them to be there. Many of the white mob tried to unsuccessfully break into the National Guard armory nearby when they saw the armed black community show up. They were trying to break in to steal guns and get more ammunition.

Humanities, N. E. for the. (n.d.). The broad ax. [volume] (Salt Lake|\\\ City, Utah) 1895-19??, June 18, 1921, image 1. News about Chronicling America RSS. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024055/1921-06-18/ed-1/seq-1/

History.com Editors. (2018, March 8). Tulsa Race Massacre. History.com. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/tulsa-race-massacre

Branigin, A. (2019, October 8). Nearly 100 years later, Tulsa begins search for mass graves from 1921 Black Wall Street massacre. The Root. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.theroot.com/nearly-100-years-later-tulsa-begins-search-for-mass-gr-1838883790

Wikimedia Foundation. (2022, April 18). Tulsa Race Massacre. Wikipedia. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulsa_race_massacre

Hi! My name is Cynthia Wing. I am 15 years old and in 10th grade. This is my first year on the Spud. I am the daughter of Maria and Henry (step-dad)...